Back Stonewall-onluste AF Stānweall sacunga ANG أعمال شغب ستونوول Arabic أحدات ستونوول ARY Disturbios de Stonewall AST Стоўнвалскія бунты BE Стоунуолски бунтове Bulgarian স্টোনওয়াল দাঙ্গা Bengali/Bangla Stounvolska pobuna BS Aldarulls de Stonewall Catalan

| Stonewall riots | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of events leading to gay liberation | |||

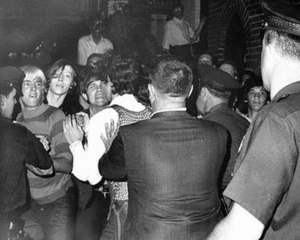

The only known photograph taken during the first night of the riots, by freelance photographer Joseph Ambrosini, shows gay youth scuffling with police.[1] | |||

| Date | June 28 – July 3, 1969[2] | ||

| Location | 40°44′02″N 74°00′08″W / 40.7338°N 74.0021°W | ||

| Goals | Gay liberation and LGBT rights in the United States | ||

| Methods | Rioting, street protests | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

|

|

The Stonewall riots, also known as the Stonewall uprising, Stonewall rebellion, or simply Stonewall, were a series of protests by members of the LGBTQ community[note 1] in response to a police raid that began in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan in New York City. Patrons of the Stonewall, other Village lesbian and gay bars, trans activists and unhoused LGBT individuals fought back when the police became violent. The riots are widely considered the watershed event that transformed the gay liberation movement and the twentieth-century fight for LGBT rights in the United States.[5][6][7]

As was common for American gay bars at the time, the Stonewall Inn was owned by the Italian-American Mafia.[8][9][10] While police raids on gay bars were routine in the 1960s, officers quickly lost control of the situation at the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969. Tensions between New York City Police and gay residents of Greenwich Village erupted into more protests the next evening and again several nights later. Within weeks, Village residents organized into activist groups demanding decriminalization of homosexuality. The new activist organizations concentrated on confrontational tactics, and within months three newspapers were established to promote rights for gay men, lesbians and bisexual people.

A year after the uprising, to mark the anniversary on June 28, 1970, the first gay pride marches took place in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco.[11] Within a few years, gay rights organizations were founded across the US and the world. Today, LGBT Pride events are held annually worldwide in June in honor of the Stonewall riots, with International LGBT Pride Day on June 28.

The Stonewall National Monument was established at the site in 2016.[12] An estimated 5 million participants commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising,[13] and on June 6, 2019, New York City Police Commissioner James P. O'Neill formally apologized for the actions of officers at Stonewall in 1969.[14][15]

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 162.

- ^ Grudo, Gideon (June 15, 2019). "The Stonewall Riots: What Really Happened, What Didn't and What Became Myth". The Daily Beast.; "New-York Historical Society commemorates 50th anniversary of Stonewall Uprising with special exhibitions and programs". New-York Historical Society. April 23, 2019.; "Movies Under the Stars: Stonewall Uprising". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. June 26, 2019. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Hoffman 2007, pp. 79–81.

- ^ Hoffman 2007, p. xi.

- ^ Julia Goicichea (August 16, 2017). "Why New York City Is a Major Destination for LGBT Travelers". The Culture Trip. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "Brief History of the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement in the U.S". University of Kentucky. Archived from the original on November 18, 2019. Retrieved September 2, 2017.; Nell Frizzell (June 28, 2013). "Feature: How the Stonewall riots started the LGBT rights movement". Pink News UK. Retrieved August 19, 2017.; "Stonewall riots". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ US National Park Service (October 17, 2016). "Civil Rights at Stonewall National Monument". US Department of the Interior. Retrieved August 6, 2017.; "Obama inaugural speech references Stonewall gay-rights riots". Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Duberman 1993, p. 183.

- ^ Carter 2004, pp. 79–83.

- ^ "Stonewall Uprising: The Year That Changed America – Why Did the Mafia Own the Bar?". American Experience. PBS. April 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ "Heritage | 1970 Christopher Street Liberation Day Gay-In, San Francisco". SF Pride. June 28, 1970. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ Nakamura, David; Eilperin, Juliet (June 24, 2016). "With Stonewall, Obama designates first national monument to gay rights movement". Washington Post. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ About five million people attended WorldPride in NYC, mayor says By karma allen, July 2, 2019. Accessed July 4, 2019.

- ^ Gold, Michael; Norman, Derek (June 6, 2019). "Stonewall Riot Apology: Police Actions Were 'Wrong,' Commissioner Admits". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ "New York City Police Finally Apologize for Stonewall Raids". advocate.com. June 6, 2019. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).